Moral Philosophy: Something is wrong, because you think it is?

Peter Chan 2018-05-04

Something is wrong, because you think it is?

On appealing to moral instincts with the classical trolley problem

In the first chapter of C.S. Lewis’s best-selling apologetics book Mere Christianity, he pointed we are almost unanimously acknowledging good and bad are objective standards that are beyond our mere preferences.

Consider a quarrel in a wet market:

A: That’s not fair, he got more fruits with the same price.

B: No. That child is an orphan, I ought to help the underprivileged.

While who’s morally right is controversial, moral standards referred here are not personal likings. Saying “I don’t like him to get this many fruits” does not have the pressing power of “Giving him more fruits is unfair”, which appeals to the moral standard of fairness. Which you know, most likely your opponent will most likely instinctually subscribe to the principle of fairness, regardless they have reasoned rigorously about this principle or not.

You may see a problem here, though. It is commonly perceived that being fair is moral, but how far the principle of fairness can extend? Do we, under all circumstances, ought to be fair? Such seems to be unlikely as there are other moral standards, say equity that we instinctually subscribe. And often the principle of fairness and equity collide with each other, it, therefore, shows to conclude what’s the right thing to do through the first moral insight is can be overly hasty.

In this article, I will be discussing how to better harness our moral instincts to judge what is the right thing to do. The approach to rely on intuition to know morality, as called ethical intuitionism, is highly controversial in its own right, but whether using intuition to deduce morality is a valid mean is out of the scoop of this article. This article assumes intuitionism and I merely intend to identify some common pitfalls of employing our moral instincts and how to overcome them.

Appealing to moral instincts as a mean of philosophical investigation

Appealing to moral instincts is not just for housewives in the wet market, but it’s also for philosophical arguments too. Objections to moral frameworks often employ reduced to absurdity arguments. Which is, in a nutshell, refuting a proposition by showing endorsing such proposition would lead to absurd (whatever that means) results.

Reduce to absurdity: Travelling to the past

For example, we could argue against the possibility of travelling to the past, because a time traveller can travel to an earlier point in time to kill himself. But if he killed himself, who’s the person that travelled to the past? Illogical consequence entails — it is concluded therefore travelling to the past is impossible. Here, “absurdity” referred to a logical paradox.

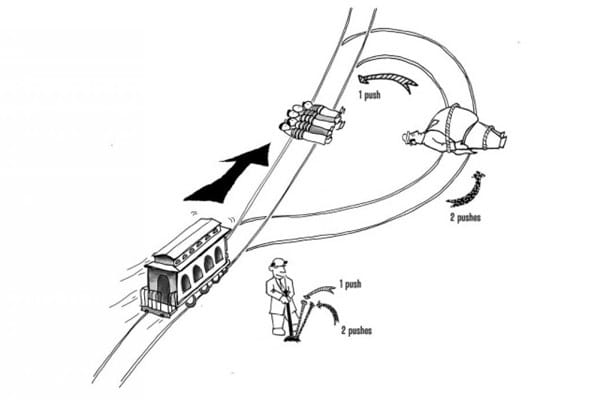

Reduce to absurdity: Fat man trolley problem

However, reduced to absurdity for moral arguments are very different in nature. Consider this objection against utilitarianism, the moral theory that argues the right action is the one that maximises happiness for the greatest number: A trolley is about to hit 5 people on a rail, as a spectator standing on a bridge, you have an innocent fat man standing aside you. You know if you pushed him off the bridge, the trolley would crash into him and the five would be saved. If the principle of maximised happiness for most beings is followed, then you ought to push the fat man down.

Opponents of utilitarianism argued if we indeed ought not to push the fat man, the principle of utilitarianism is rejected. In a short form, the argument can be written as follows:

1) IF utilitarianism THEN push the fat man

2) Ought NOT to push the fat man

Therefore, NOT utilitarianism

1) is derived from the nature of utilitarianism, as sacrificing one’s life would bring lives to five. However, how is premise 2) being supported? Assuming the principles of utilitarianism are being endorsed, then the sole criteria for determining whether an act is right is whether it maximises happiness (for all). Pushing the fat man off is neither contradictory to this principles, nor will it lead to logically impossible ramifications like the example of travelling to the past. The conclusion for us ought to push the fat man is considered as “absurd”, nevertheless, “absurdity” here referred to a very different thing — rather than a logical problem — “absurdity” here refers to the ingrained revulsion when we evaluate the situation here.

Then, on what basis, we conclude that we ought not to push the fat man?

A brief overview of moral instinct

We conclude so on the basis of moral instinct — the instinctual moral revulsion I have mentioned. Which is, as a moral agent, we have the ability to perceive whether an act is moral or not. I here would like to draw the distinction between exercising moral instinct and arbitrarily defining what’s being morally good or not. Moral instinct, here I mean a perception that moral agents have that spontaneously and involuntarily apprehend moral statements. Such as “do good and avoid evil” is a statement any moral agent would apprehend as moral, as much as “If A, then A” would be endorsed by any logical agent, without external support whatsoever.

To what extent though, we can rely on our moral instinct? This is a difficult question, but the answer cannot be that we can trust it absolutely in every scenario. We can apprise intuitively that “1 + 1 = 2” is true doesn’t entail we can do the same to a complex, 10 paged mathematical proof, even that proof seemed intuitively true. Analogously, apprising intuitively that “do good and avoid evil” is justified, but the same doesn’t apply appraising intuitively that “abortion is bad”.

But after all, issues such as abortion, that are not self-evidently good/bad are those needed to be tackled by philosophy. How do we ponder on these if we can only rely on moral instinct to a certain degree? Philosopher Francisco de Suarez claimed moral precepts can be divided into three categories:

1) Those that are known immediately (e.g. “do good and avoid evil”)

2) Those that require experience to know, but are self-evident (e.g. “inflicting pain on others for no good reason is morally bad”)

3) Those that are not self-evident, but can be derived from more basic moral precepts that belong to 1) or 2) (e.g. “torturing an animal for no good reason is bad”)

Reappraising the fat man objection

Let’s revisit the fat man objection mentioned under Suarez’s framework. The proposition that “you should not push the fat man off the bridge to save five people” are neither category 1) and 2) in Suarez’s framework. For moral propositions in category 1) and 2) are not derived from other more basic moral precepts, in other words, statements like “do good and avoid evil” have the properties of irreducibility. They could not be explained why it is so, but through immediate moral apprehension (or with experience, for 2) statements).

However, we can give reasons for why “you should not push the fat man off the bridge to save five people” (e.g. killing a human is bad). It is, however, noteworthy that the reasons that we scrutinise here should be based on the difference of the classical trolley problem and the fat man problem, because, at least for most people, the classical trolley case does not elicit the same intense sense of repulsive moral sense in the fat man case.

Therefore, in the discussion of this matter, we should focus on the idiosyncrasies in the fat man case that is used as an argument to counter utilitarianism. For instance, “one shall not take any action that would take others’ life” is extraneous for the discussion, for in the classical trolley case this moral proposition is violated, yet in general, our moral instincts would not deem that as “absurdly immoral” and thus reject utilitarianism.

I will now outline the reasons, as far as I can think of, that uniquely accounted for the moral absurdity of the fat man case:

Mainly, pushing an innocent civilian off the bridge brings negative soceitial ramifications. Imagine living in a society, where it is permissible to push anyone down from a bridge, as long as it serves a greater good for a greater number. It is a society where individuals have their agency deprived, or simply put, living in a white terror.

I would argue, walking on a bridge is an activity that civilians would engage on a daily basis, and it is the sense of potentially being hurt anytime, over the other reasons, that elicited the moral instinct that pushing the fat man down is not right.

Considering this classical moral dilemma, of course, we have to discuss the famous Kantian objection that humans should not be regarded as means, but for ends in themselves. Do we instinctually regard it is not just to treat other as means? I believe this is not the case so — take a look at the loop variant of the trolley problem:

In this case, the man on the rail is serving a similar purpose compared to the fat man on the bridge: to stop the trolley with his body. The mere difference between the two cases is that the victim disappeared in different locations initially: one lied down on the rail mystically, which is an experience that probably I and you haven’t experienced; whereas another one was on a bridge, and I am pretty sure all of us have been on a bridge before. This difference, namely how we ordinary civilians are likely to be involved, may cause the differential appraisal of moral instinct. And such differential appraisal makes sense: pushing the fat man off the bridge would promote a sense of vulnerability, or white terror so to speak in the society.

In this case, the man on the rail is serving a similar purpose compared to the fat man on the bridge: to stop the trolley with his body. The mere difference between the two cases is that the victim disappeared in different locations initially: one lied down on the rail mystically, which is an experience that probably I and you haven’t experienced; whereas another one was on a bridge, and I am pretty sure all of us have been on a bridge before. This difference, namely how we ordinary civilians are likely to be involved, may cause the differential appraisal of moral instinct. And such differential appraisal makes sense: pushing the fat man off the bridge would promote a sense of vulnerability, or white terror so to speak in the society.

Of course, one might criticise it is a hasty conclusion that our moral intuitions disapprove pushing the fat man off the bridge because of the probability of an ordinary civilian being involved is high. My response to this criticism would be as following: First, through comparing the loop variant and the fat man variant of the trolley problem, there seems to be no better explanation than the likelihood to be involved that accounts the resulted difference in the moral appraisal.

Moral heuristics: The fairly accurate moral GPS

Second, it makes sense that humans instinct are developed this way around — given the constraints when we are making moral decisions. We are humans, although we are capable of developing sophisticated moral frameworks with a combination of reasonings and instincts. But in most cases when we need to make a moral judgement in a split-second, instincts, instead of reasonings are what remains. Say, it’s simply impossible to do a long-winded debate on why fairness is a virtue when you’re trying to convince the shopkeeper to give you more vegetable.

Nevertheless, does it mean we can let go of moral considerations whenever there is no time to meditate on esoterical moral principles? Utilitarian philosophers like John Stuart Mill and Henry Sidgwick think this is less than ideal, and it is necessary to follow some moral rules of thumb, that when followed, will most likely produce more good than harm. In which, our moral instincts are largely abided by these rules, or in other words moral heuristics. These moral heuristics do serve a value: an ancient Chinese philosopher, Mencius once said: “If men suddenly see a child about to fall into a well, they will without exception experience a feeling of alarm and distress.” (人乍見孺子將入於井,皆有怵惕惻隱之心。)

I would argue “don’t push an innocent person off a bridge” is one of these moral heuristics. For most of the cases, pushing people off a bridge would do more harm than good. Say, if we don’t have the moral instinct that dissuades us from pushing others off a bridge through a non-rational route, who knows what’d happen if we have a fierce argument with a person on a bridge, so fierce that it shuts down our rational faulty?

New lens to the fat man problem

With the analysis above, we come to the following conclusions:

1) Moral instincts tend to disapprove pushing the fat man

2) In consequentialists perspective, there is reason(s) to argue against pushing the fat man, bearing to non-moral facts such as whether pushing the fat man would cause greater societal distress

3) Humans often use moral heuristics to make moral judgements in daily life

It can be further concluded that instinctual judgement of disapproving pushing the fat man has some legit considerations. Say it may threaten the social autonomy as I have analysed above. Whether the societal harm would outweigh the benefit that four lives being saved is really another debatable issue that would perhaps never reach a unanimous answer.

Yet, I’d like to point out analysing societal harm depends on the social context. Under some context, it may be justified to push the fat man down, while under some are not. Whereas the original form of the fat man problem didn’t provide the social context of the situation, yet still our moral instincts are able to render judgement, which I’d call an omission.

To support my stance, I’ll provide an example of social contexts that would plausibly affect the judgement of common moral instincts.

Multiple Bridges

You’re a member of a village comprises of 601 villagers. Fortunately (or unfortunately) except you, all other members are involved in the fat man problem, assuming every one of them is of equal importance to you so you don’t have to consider the probability of your close relatives being involved. 100 villagers are randomly assigned to be fat men on 100 bridges and the remainders, 500 if them, are lying on 100 different rails. How would you do? Would you push all the fat men, or push none, or push some?

How does your instinct react to this scenario? For me, it made me more inclined to push all the fat men — and I guess it would be the same for same for most people as you start to consider the difference in societal impact between the two cases.

Note that this multiple bridges scenario is not a new variant of the trolley problem, rather, it’s a piece of supplemental information of how the fat man variant problem is enacted. This is exactly identical to the original paradigm except with societal context supplied.

If additional societal context would incline our moral instinct towards pushing, or otherwise, it shows moral instinct of this particular sort is a moral heuristic. Because a crucial characteristic of moral heuristic, or heuristic of any sort, is that information-gaps are being filled by the heuristic.

In short, the concluding pushing the fat man is unjust instinctually is largely a moral heuristic as I have shown there might be missing pieces of information that may invert the moral instincts’ appraisal. It follows that this particular objection to utilitarianism is futile because the proposition that “one ought NOT to push the fat man” is context-dependent and moral instincts would not necessarily apprise it as true — when an additional context is supplied.

Wrapping up: reason with our moral instincts

We have gone through the journey of scrutinising a famous moral argument that appeals to moral instinct. What can we learn from it?

I think Elon Musk’s words put it as best — although he spoke not of the domain of morality, it is of striking relevance when we consider moral problems:

“Boil things down to their fundamental truths and reason up from there, as opposed to reasoning by analogy.” — Elon Musk

Moral instincts, too, often function by analogy. When it approaches a new case, it recalls the cases that we are familiar with and renders the judgement.

Push to kill an innocent fat man? In the real world, 99% of such action do more bad than good to our society. While in our daily life it is reasonable not to push the fat man, given that we don’t have the time and mental resources to do the cost-benefit analysis and thus can only rely on our primitive instinct.

But, philosophical meditation is different. We do have the time and mental resources. For any person making his conquest to a moral question with the intuitionist approach, I think he should keep boiling down the question until it becomes something that is self-evident (Type 1 or 2 in Francisco de Suarez’s framework). And, especially in metaphysic ethical questions, avoid the temptation to justify an act in a new context, when it is agreed that that particular act is just another contexts.

Say, as a Christian, I am highly sceptical of the doctrine of eternal damnation. I often encounter people drawing analogy between secular punishment (i.e. imprisoning a murder), and the “divine” punishment, and through this justifying the latter. We virtually have a consensus on the legitimacy of secular punishment — for it serves the purpose of correction AND protection of the others, through segregating/killing the trespassers. But hell would neither correct one for the better nor protect any being, would this kind of punishment be justified?

What’s the sake of an eternal hell?

Punishment for punishment per se?

Can it be boiled down? (Reduced to more fundamental moral principles)

For sure, some people would deem retributive justice as something self-evident. But can it be spoken of to the degree of certainty of that our instinctual apprisial of “Do good and avoid evil”?

Indeed, these are not easy questions. But as a person in an ever-evolving society that becomes more divided over moral issues, such as abortion, veganism, and others. The issues are hardly one-cut right or wrong by the acts themselves, but the morality of these issues bear on the consequences and factual truth. For example, if science shows fetuses have no consciousness, then the moral judgement of the case would be very different .

It is, therefore, of vital importance to boil down these issues to fundamental precepts, instead of being overwhelmed by the first instinctual response that is often habituated by the society. Such that, our moral instincts can be of better leads to the true good.